Rogue Regulator: PMPRB’s false narrative is driving dangerous drug price controls

Brett Skinner PhD

Canadian Health Policy Institute 2021. ISSN 2562-9492 https://doi.org/10.54194/YQYB2454 www.canadianhealthpolicy.com

Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Price Controls

- International Price Referencing

- Pharmacoeconomic Value Assessment (PVA)

- Net Ceiling Prices

- Regulatory Impact on Prices

- Chapter 3: Price and new drug launches

- Chapter 4: Price and industry-funded pharmaceutical R&D

- Chapter 5: Prices for patented medicines

- Prices in the PMPRB7

- Prices in 14 PMPRB countries

- Chapter 6: Patented medicines expenditure (PMEX)

- Chapter 7: Cost v Benefits

- Chapter 8: Rogue Regulator

- False Narrative, Risky Regulation

- Public Accountability and the Duty of Neutrality

- About the Author

- References

Preface

There is a consensus among economists that government price controls are generally ineffective at achieving their intended purpose, tend to distort the allocation of resources, and often produce inequitable social outcomes.[1] It is also widely observed by economists that price regulation depresses pharmaceutical innovation, which affects health outcomes, resulting in higher expenditures on other forms of medical care.[2] [3] Economists generally agree that efficient spending on health is an investment in human capital which is a contributing factor to economic productivity, and that pharmaceutical innovation has been a major contributor to better health outcomes, improved quality of life, and longer life expectancy.[4]

So why is the federal government imposing extreme price regulations that will discourage drug-makers from launching new innovative medicines and investing in pharmaceutical research in Canada?

In January 2022, the government is introducing new price control guidelines at the request of the federal regulator known as the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board or PMPRB. The regulator estimated the changes will cut Canadian prices for patented medicines by more than half the current level. That would make our prices the lowest in the world.

Since 2015, the agency has run a communications campaign to justify the amendments, raising alarms about high prices for patented medicines and the impact on healthcare costs. At the same time, it has insisted that the changes will not reduce the availability of new medicines or impact industry investment in pharmaceutical research in Canada. In a 2020 article, the Executive Director of the PMPRB wrote “there is no evidence of a link between pricing, research and development, and access to medicines”.[5]

It is hard to believe that mandatory price cuts of such severe magnitude won’t negatively impact industry decisions about whether Canada is a priority market for new therapeutic products, or whether it is the best place to spend scarce research dollars. The government is wrongly assuming that the industry will continue to prioritize our market at any price decreed by the PMPRB.

The government is also not thinking about how long it took to build the clinical science infrastructure in Canada. The regulations risk eroding valuable institutional knowledge and technical expertise, and it will be expensive to restore.

The truth is the regulator is aware of evidence that contradicts its narrative justification for amending the regulations but seems to have chosen to suppress it. Moreover, PMPRB has not provided parliament with any evidence to support its narrative.

In this book I review some of the evidence the PMPRB said did not exist. I also discuss the rogue behavior of the agency.

The Government is making these changes based on advice from a regulator that has a conflict of interest. The PMPRB not only initiated the regulatory changes, but also wrote the new rules, self-evaluated the impact on prices, managed public consultations, and controlled the flow of information to parliamentarians.

Important stakeholders and prominent academics have raised questions about the PMPRB’s commitment to its duty of neutrality as a public agency. The Federal Court of Appeal even criticized PMPRB for bending its own rules, breaching its jurisdiction and for obfuscating behavior, which makes it impossible to review its administrative decisions.

The Parliament of Canada is obligated to reconcile the PMPRB’s narrative with the evidence presented in this book. It should conduct a formal review of the agency’s relevance. Due consideration should be given to retiring its mandate.

Brett Skinner, PhD

[Chapters 1-2 excerpted.]

Chapter 1: Introduction

The prices of patented medicines sold in Canada are regulated by a quasi-judicial agency of the federal government known as the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB). In January 2022, the Government of Canada is implementing major changes to the PMPRB, affecting the way drug prices are regulated. The changes are dangerous and unnecessary.

The Board was established as part of the reforms to the Patent Act 1985, which strengthened intellectual property rights protections for pharmaceuticals. The PMPRB was the government’s policy response to critics who were concerned that the reforms would allow patent-holders to abuse monopoly pricing power.

It is an independent, arm’s-length agency of Health Canada, but is not subject to ministerial direction. The agency reports directly to Parliament. Within the limits of the Act and the Regulations, PMPRB rulings and orders have the same enforceability as the Federal Court. Its regulatory authority applies to all drugs with active patents, and which are sold in Canada, and includes both public sector and private sector sales.

The agency has a mandate to prevent innovative pharmaceutical companies (aka “patentees”) from charging excessive prices for patented medicines. The Regulations require the Board to use international referencing to determine whether Canadian prices are excessive. The Board is empowered to assess financial penalties against patent-holders for charging prices that are, in the Board’s opinion, excessive. The regulations do not define what “excessive” means. The Board has the freedom to use any reasonable methods to define excessive prices.

The second part of its mandate is to monitor and report on prices for patented drugs. The regulator also reports the research and development (R&D) spending and sales trends of patentees because the federal government strengthened pharmaceutical patents with the expectation that it would attract foreign direct investment in R&D to the country. In exchange for protecting the property rights of patentees, the government expected the industry to spend 10% of its Canadian sales on R&D in Canada.

It is important to note that the PMPRB is an aberration. No other industry in Canada is subject to direct price regulation. Nor is the protection of intellectual property rights conditional on the R&D to sales ratio for any other business sector. The Board has no international counterpart. No other country regulates drug prices using an agency like the PMPRB.

The pending regulatory changes will make Canada a more extreme outlier because the new rules are more severe than any other regime in the world. Nothing like this has been tried anywhere else.

The upcoming changes were first proposed by the PMPRB in 2015. A long process ensued, which included several public consultations, culminating in the final regulations being announced in August 2019.[6] [7] The new regulations were to come into effect on July 1, 2020, but the government delayed implementation until January 1, 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In December 2020, the government announced a second delay extending to July 1, 2021. Most recently, in June 2021, the government announced a third delay until January 1, 2022.

The purpose of the regulatory amendments is clear. According to Health Canada, “The Government of Canada is firmly committed to… taking action to significantly lower the cost of prescription drugs… This important work includes reducing the cost of patented drugs through the modernization of the pricing framework under the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board.”[8]

How will the regulations affect patented drug prices? The federal government’s Strategic Policy Branch estimated that the changes will cut the maximum prices allowed for patented medicines by more than half the current price ceiling.[9]

Industry, patient groups and researchers have warned that the lower price limits could cause pharmaceutical companies to deprioritize the Canadian market when launching new medicines and will delay access to innovative therapies for Canadian patients. They also expressed concerns the new regulations will discourage industry investment in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) in Canada.

The PMPRB rejects such concerns. Citing a lack of evidence, it stated that “prices do not appear to be an important determinant of medicine launch sequencing” and “The link between high domestic prices and industry investment has not been demonstrated.”[10]

Despite the PMPRB’s assertion, there is in fact plenty of evidence. Labrie (2020) conducted a systematic literature review and found 44 peer-reviewed studies showing that drug price controls reduce the availability of innovative drugs and/or discourage industry investment in pharmaceutical R&D.[11]

The Government of Canada is wrong to assume that the changes are benign. The new price limits are hostile to innovation and will disincentivize pharmaceutical firms from prioritizing the Canadian market when launching new medicines. Many advanced therapies will likely be available to patients in other countries for years before becoming available to Canadians.

Industry investment in pharmaceutical R&D is driven by multiple variables. There is quite a lot of empirical evidence that the price ceiling for patented medicines is an important factor in company decisions about where to locate industry-funded clinical research. The PMPRB regulatory changes will likely cause a substantial decline in the number of industry-funded clinical trials in Canada.

The amended regulations are not only risky, they are not even necessary. The prices of patented medicines in Canada are not excessive. The truth is, that patented medicines have accounted for a stable, small percentage of national health expenditures (NHEX) and gross domestic product (GDP) for more than 30 years, and Canadian prices for patented medicines fall in the middle of prices in comparable countries, and appropriately reflect the country’s GDP per capita.

Indeed, it is reasonable to ask whether Canada needs a federal drug price regulator at all? The PMPRB’s relevance is questionable because its function is redundant. Several other agencies are involved in regulating the efficacy and price of new drugs.

Before any new drug can be sold in Canada, it must first be approved by Health Canada, which assesses the safety and therapeutic effectiveness by reviewing published clinical evidence about the drug.

Following successful approval by Health Canada, all new drugs must pass through health technology assessment (HTA) at the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH), which conducts a review of the evidence regarding the cost effectiveness of the drug using pharmacoeconomic techniques and concepts like cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY). CADTH makes recommendations regarding reimbursement on behalf of all federal and provincial public drug plans, except Quebec which utilizes its own HTA agency known as the Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS).

Following this, all new drugs are subject to price negotiation with the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (PCPA), which acts as a monopsony purchaser on behalf of every federal and provincial public drug plan. The PCPA negotiates prices that are well below the list prices permitted by the PMPRB.

It is hard to justify the need for a federal price regulator when new drugs are already subject to a complex process of approval and negotiation that results in prices that are lower than the ceiling prices imposed by the regulator. It is increasingly obvious that the PMPRB’s mandate is obsolete.

This explains why the regulator so aggressively advocated for the regulatory changes. The PMPRB is engaged in a desperate attempt to preserve its bureaucratic relevance. The analysis presented in this book suggests the PMPRB has used a false narrative to drive dangerous changes to drug price controls in Canada.

In Chapter 2 I briefly describe the pending regulatory changes and offer a critical analysis. In Chapters 3 to 6 I review some of the evidence that the PMPRB has ignored regarding the key elements of its narrative including: the link between price and new drug launches, the correlation between price and industry funding for clinical research, whether prices are too high in Canada, and whether those prices are causing unsustainable costs for the healthcare system. Chapter 7 reviews a small sample of evidence demonstrating the benefit of pharmaceutical innovation, something which too often gets left out of discussions about the cost of patented medicines. Chapter 8 sums up my final thoughts about the rogue behavior of the PMPRB, including its false narrative and its disregard for public accountability and the public service duty of neutrality.

Chapter 2: Price Controls

International Price Referencing

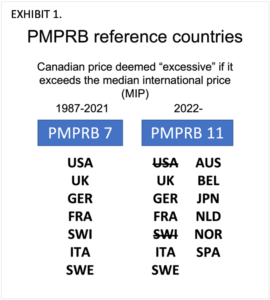

The PMPRB uses international price referencing as one of its methods, to regulate against excessive prices for patented medicines sold in Canada. Under the current regulations, the Canadian price is deemed to be excessive if it exceeds the median international price (MIP) for the same drug sold in a specified group of reference countries.

Known as the PMPRB7, the seven countries currently specified by the regulations for international price referencing to Canada include France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The new regulations change the mix and the number of reference countries used for price comparison. The PMPRB7 expands to the PMPRB11 by removing the United States and Switzerland and adding Australia, Belgium, Japan, Spain, Netherlands, and Norway. [EXHIBIT 1]

The changes are associated with several problems which the PMPRB has failed to bring to the attention of parliament. First of which is that the new PMPRB11 countries are not an objective comparator group. The PMPRB’s selection of reference countries was arbitrary. To be included, the agency required the countries to be like Canada on the basis of GDP per capita, population, and market entry of new products. The inclusion criteria specified by the PMPRB were inconsistently applied.

Take the GDP per capita criteria for example. Average income varies widely across current and former PMPRB reference countries. This makes it nearly impossible to exclude any of the former reference countries on the basis of differences or similarities related to GDP per capita.

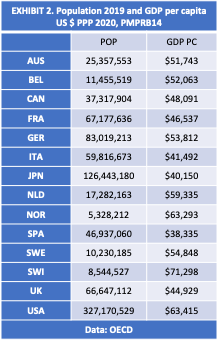

EXHIBIT 2 shows data sourced from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for GDP per capita denominated in US dollars at purchasing power parity (PPP) for each of the seven current and six new reference countries to Canada.

Notice that, in 2020 GDP per capita in the United States ($63,415) and Norway ($63,293) was 32% higher than Canadian GDP per capita ($48,091). Yet the US was excluded, while Norway was included as a reference country.

Inconsistencies in the application of the population criteria are also obvious. Comparing the most recent population data from the OECD [EXHIBIT 2] shows Sweden at 10.2 million, Switzerland at 8.5 million, and Norway at 5.3 million. Yet Switzerland was excluded, while Sweden and Norway were included as reference countries.

The United States population (327.1 million) is 9 times larger than Canada (37.3 million), but Canada’s population is 7 times greater than Norway. Yet the US was excluded, while Norway was included.

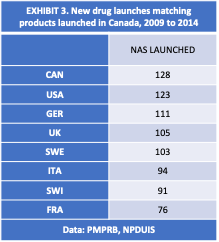

PMPRB data [EXHIBIT 3] show that the US has the highest degree of commonality with Canada regarding the market entry of new drug products. Of the 128 new active substances (NAS) launched in Canada between 2009 and 2014, 123 were also launched in the US. The same data show that of the 128 NAS launched in Canada, 91 were also launched in Switzerland, which is higher than the 76 NAS launched in France.[12] Yet France was included as a reference country by the PMPRB while the US and Switzerland were excluded.

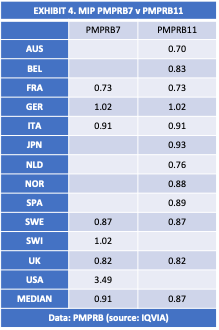

A quick look at the impact on the MIP from the new PMPRRB11 is shown in EXHIBIT 4. Using data published by the PMPRB it is apparent that relative to the PMPRB7, the PMPRB11 is overrepresented by lower priced markets. The PMPRB7 group of countries had balanced representation from higher priced and lower priced markets. The exclusion of higher priced markets and the inclusion of additional lower priced markets artificially depresses the MIP. The difference is about 4% according to these data.[13]

Incidentally, it is worth noting that excluding high-price markets from the PMPRB reference countries, undermines the value of the Board’s reporting mandate because it deprives policymakers of vital information about the effect of price regulations on the availability of new medicines, industry investment in clinical research, and the development of an innovative domestic pharmaceuticals industry in Canada. For example, the United States has the highest drug prices in the world, but Americans get the earliest access to new medicines and the country attracts the highest levels of industry investment in research and development of innovative pharmaceuticals. It serves the public interest for policymakers to be informed of this reality and the trade-offs associated with alternative policy approaches.

However, a more important problem is that international price referencing is a moving target. The position of the MIP, bilateral price ratios and country ranks are sensitive to the data sources and methods used to calculate them. To illustrate this, we can look at some data from a recent study I conducted. [14]

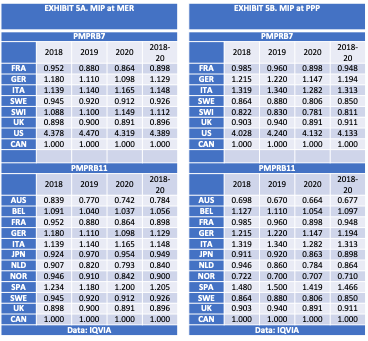

The data in EXHIBITS 5A-5B are from IQVIA, the same source used by PMPRB for the data in EXHIBIT 4. However, the data sample and methods differ from the PMPRB as I explain in Chapter 5.

Bilateral foreign-to-Canadian price comparisons were limited to symmetrical drug molecules with the same domestic patent protection status. The analysis used a standardized unit of measure for calculating foreign-to-Canadian price ratios that is comparable across varied dosage strengths, pack sizes and sales weights: defined as gross sales at manufacturer list prices per standard unit sold.The data include the average foreign-to-Canadian price ratios in the PMPRB7 and PMPRB11 countries for the patented drugs most likely to exceed the sales threshold triggering a pharmacoeconomic value assessment (PVA), which I describe in the following section. The sample included 100 top selling patented medicines in Canada from 2018 to 2020 and is estimated to represent close to 50% of the total market for sales of patented medicines in each year.

The median international price in each year is highlighted. Canada’s ratio is held constant. Prices are denominated in US dollars at market exchange rates (MER) and at PPP.

The results clearly show significant variance between the estimates of foreign-to-Canadian price ratios. The MIP fluctuates depending on the data source, data sample, method, currency adjustment and year. Notice in EXHIBITS 5A-5B that Switzerland flips from a high-cost market to a low-cost market when prices were denominated at PPP versus MER. Note also that the magnitude of the change in MIP associated with the move from PMPRB7 to PMPRB11 reference countries is larger using this method versus the method used in EXHIBIT 4.

While the regulations specify the countries that the PMPRB must use for price referencing, the agency is pretty much free to use any method it chooses to define excessive prices for the purpose of enforcing regulations. The MIP could be a moving target depending on whether the regulator uses MER or PPP to denominate prices, or a different time period (for example, the most recent year, or the average of the most recent three years), or the average prices of all patented medicines versus a sample of patented medicines that are subject to PVA, etc.

The regulatory metrics are fluid, yet they have the force of law. As I explain further in Chapter 5, there are other limitations associated with the method used by the PMPRB that challenge the objectivity of the regulations. The limitations demonstrate the folly of the notion that regulators can set prices without distorting the market. The use of methods like international price referencing merely provides false scientific legitimacy for what are really just arbitrary rules. As I will discuss in the next section, the same thing can be said about PVA.

Pharmacoeconomic Value Assessment (PVA)

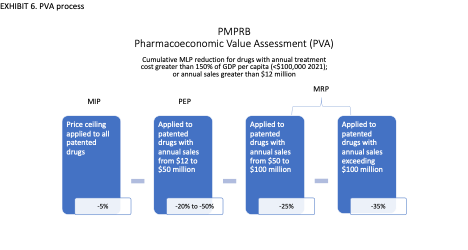

In addition to the PMPRB11 median international price test, the price control guidelines introduce a pharmacoeconomic value assessment (PVA) for new medicines. Patented drugs priced higher than their computed pharmacoeconomic value will be subjected to dramatic price cuts. The regulations also impose profit controls on drug products with sales revenue exceeding defined thresholds.

Pharmacoeconomic analysis is used in Canada and other countries to inform reimbursement negotiations. But it is unsuitable for use in regulation because it is based on data, metrics, and methods for which there are no agreed standards and which at best produce subjective, assumption-dependent estimations. There are well-known conceptual and technical problems and limitations associated with pharmacoeconomic analysis.[15] [16] [17] The new guidelines have not resolved these problems.The price control guidelines pertaining to PVA are very complicated. A simplified illustration of the process is shown in EXHIBIT 6. PVA applies to new drugs that have a 12-month treatment cost greater than 150% of GDP per capita. First, a Maximum List Price (MLP) ceiling is set according to the MIP of the PMPRB11 countries. The MLP is reduced to the Pharmacoeconomic Price (PEP) based on the regulator’s assessment of therapeutic benefit, and cost-effectiveness measured as the cost per Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) (aka the Pharmacoeconomic Value Threshold, or PVT). The MLP is further reduced for the size of the market, defined by sales revenue thresholds determined by the regulator. The final ceiling price allowed under the regulations is called the Maximum Rebated Price (MRP).

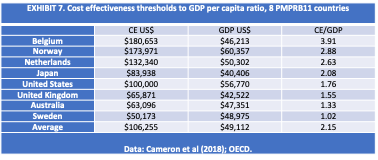

For example, the PEP is derived from the drug’s cost per QALY, which the guidelines refer to as the PVT, but is known elsewhere as the cost-effectiveness (CE) threshold. There is no international standard or consensus regarding the appropriate CE threshold. A 2018 study reviewed the CE thresholds in 17 countries including 8 of the PMPRB11 [EXHIBIT 7]. CE thresholds ranged from 102% of per capita GDP in Sweden up to 391% of per capita GDP in Belgium. On average CE thresholds were 215% of per capita GDP.[18]

Subjectivity is obvious in the evolution of the PVA and PVT thresholds proposed by the PMPRB. Under the regulatory changes that are to go into effect in January 2022, new drugs with prices exceeding 150% GDP per capita (or about $87,000 in 2020 based on GDP per capita of CAN$58,000.[19]) are subject to the PVA. This is higher than the original PVA threshold proposed by the PMPRB in early draft regulations, which was only 50% of GDP per capita. Under the new regulations, PVT levels range from 170% to 340% of GDP per capita ($100,000 per QALY to $200,000 per QALY). This is up from 60% of GDP per capita originally proposed in earlier drafts.[20]

Similarly, there is no international consensus regarding the appropriate value of a QALY. QALY is a weighted numerical value which is assigned to various potential health conditions. The values are subjectively determined based on responses from public and expert opinion surveys, using a variety of methods of which there is no standard because each are vulnerable to significant limitations. The simplest method asks respondents to weight the importance of health conditions on a scale from zero (death) to one (perfect health). Other methods ask people to choose between alternatives involving a trade-off between quantity and quality of life; or to weight improving the life expectancy of people with full health, versus improving the health expectancy of people with an illness/disability; or to choose between no treatment, and the risk of a treatment with two possible outcomes, one worse and the other better than no treatment. Such methods are not objectively scientific and are susceptible to ethical problems, knowledge limitations and potential bias.[21]

To get to the final MRP, the Guidelines also impose mandatory additional price reductions for products that generate more than $50 million in annual sales in Canada. PMPRB refers to these price cuts as the market size adjustment factor.

This feature of the guidelines is tantamount to the regulation of profits, not the regulation of prices, and goes well beyond the boundaries of the PMPRB’s mandate. There is no precedent for this in any industry in Canada. The policy is extremely hostile to innovation because it imposes diminishing returns on commercially successful products. It will amplify the disincentives for launching new medicines in Canada.

Net Ceiling Prices

The new Guidelines also require patentees to report price and revenues net of all price adjustments. Prices net of rebates will be used to set the ceilings for new medicines. Previously the regulations applied price controls to the manufacturer’s ex-factory list price. Manufacturers negotiated rebates with public drug plans and private insurers below list price. The largest discounts were typically offered to public payers due to their superior bargaining power.

There is no published source of product-level data on final prices because rebates are confidential business information protected by contract and constitutional law. In two separate cases, the Federal and Quebec courts recently affirmed these rebates to be constitutionally protected private information. In both cases, the court struck down provisions in the regulatory amendments requiring patentees to disclose rebated prices. The PMPRB is appealing both cases.[22] [23]

The RIAS cited price discrimination as a rationale for regulating net price ceilings,

“In Canada and other developed countries, it is common practice for medicine manufacturers to negotiate confidential rebates and discounts off public list prices in exchange for having their products reimbursed by public and private insurers. This empowers manufacturers to price-discriminate between buyers based on their perceived countervailing power and ability to pay.”[24]

The statement reveals that the PMPRB thinks part of its mandate is to ensure private insurance companies do not pay higher prices for patented medicines than public drug plans pay. However, its actual mandate is to set ceiling prices not final prices. Imposing a single market price would be a mistake. Price differentiation is an economically efficient way to achieve socially equitable outcomes. [25] [26] [27]

At the international level, drug prices tend to be higher in wealthier countries and lower in less wealthy countries. Pharmaceutical companies use price discrimination (or differentiation) to maximize profits across markets with different average incomes. However, the higher prices charged in wealthier countries subsidize lower prices in less wealthy countries, making it possible for consumers to access more medicines that they would otherwise be able to afford.

Price discrimination between payers within a market also produces socially equitable outcomes. In Canada, the ability to charge different prices to public and private payers has contributed to more equitable outcomes than would have occurred under a single market price.

The Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (PCPA) conducts joint price negotiations with pharmaceutical manufacturers on behalf of all Provincial and Territorial public drug plans and cancer care agencies, plus the Federal Non-Insured Health Benefits, Correctional Services of Canada and Veterans Affairs Canada. The PCPA leverages monopsony bargaining power to achieve uniform pricing and reimbursement conditions for public payers. Public drug plans pay prices that are much lower than the manufacturers list price. Ontario’s Auditor General reported that the province’s public drug plan received rebates averaging 36% on brand name drugs in the fiscal year 2016/17.[28]

Public sector discounts are made possible because pharmaceutical companies can charge higher prices to private sector payers like insurance companies. While private payers are free to negotiate rebates with manufacturers, there is little evidence that they obtain rebates as large as those reported for public payers. However, private drug plans cover economically secure populations, whereas public drug plans serve economically vulnerable populations. The higher prices charged to private payers subsidize the lower prices negotiated with public payers.

Price discrimination therefore makes it possible for public payers to cover more drugs for more vulnerable people than they would otherwise be able to afford within tax-funded budget constraints. It achieves this without reducing utilization among privately insured populations, who are early adopters of new drugs and thereby fund future innovation.

Differential pricing has likely increased the availability of new drugs in Canada. The potential to obtain higher prices in the private market encourages pharmaceutical manufacturers to launch new drug products in Canada earlier than would otherwise occur with uniform prices set at public market levels.

The fact that public payers have more bargaining power than private payers does not justify the regulations. Private insurers have significant bargaining power relative to pharmaceutical manufacturers. High-cost drugs can cause affordability challenges within some individual drug plans, but this occurs mainly because of insufficient risk pooling. Many employer-sponsored drug plans essentially self-insure their employee population, utilizing the insurer merely for administrative services only. Industry-wide risk pooling is a solution. Government could make it mandatory for all employer-sponsored drug plans to participate. This approach would be more legitimate than using the PMPRB as a cost manager for private sector drug plans.

Regulatory Impact on Prices

According to the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS) published in the regulations, the combined effect of replacing the PMPRB7 with the PMPRB11, introducing PVA, and applying the price controls to net prices, will reduce the maximum allowable prices for high-cost medicines by 52%.[29] The impact is likely to be much larger.

The RIAS indicated that changing the reference countries will reduce the revenues of high-priority medicines by 4.5%. In a separate analysis, the regulator estimated that, if the new PMPRB11 were implemented in 2019, the MIP would have been 19% lower than Canadian prices.[30] Contrast this with the data from my study of the top 100 selling patented medicines, which showed the MIP could range from 10% higher to 5% lower than Canada depending on whether prices were denominated at MER or PPP. Estimates of the MIP are also sensitive to other methodological differences identified later in Chapter 5, making it difficult to estimate the price impact with certainty.

In addition, the regulatory impact analysis estimated that the application of the three new PVA factors (therapeutic criteria, PVT, profit controls) is expected to further lower the price of new high-priority medicines by more than 40% on average. However, the regulations specify mandatory price cuts up to 50% from applying the therapeutic criteria and PVT, and another 35% from profit controls.

The RIAS also estimated that applying price ceilings to the net price would result in a further 7.68% reduction in projected patented medicine costs. The estimate assumed that rebated prices were 10% lower than the list prices reported to the PMPRB. Yet, public payers routinely receive rebates that are four times as large. If the regulations apply price controls to net prices, it will extend public sector rebates to private sector payers and amplify the estimated impact on prices.

Expectations of a deeper impact from the regulations are also supported by results from two independent studies which examined the Guidelines and retrospectively applied them to the case of a recently launched medication for a rare disorder. The researchers found that the Guidelines would have imposed price ceilings from 61% to 84% lower than the actual maximum allowed for those drugs.[31] [32]

[… To read the rest of this book click the download button at the top of this article.]

About the Author

Brett J Skinner (Ph.D., M.A., B.A.)

Brett J Skinner is the Founder and CEO of Canadian Health Policy Institute (CHPI) and the Editor of CHPI’s online journal Canadian Health Policy. Dr. Skinner was Executive Director Health and Economic Policy at Innovative Medicines Canada (2013 to 2017); and CEO (2010 to 2012) and Director of Health Policy Studies (2004 to 2012) at Fraser Institute. Dr. Skinner has B.A. and M.A. degrees from the University of Windsor with joint studies at Wayne State University, and a Ph.D. from Western University where he has lectured in both the Faculty of Health Sciences and the Department of Political Science. In 2015 Brett was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s disease. He has both an academic interest and a personal health stake in government choices affecting future medical innovation.

References

[1] Alston, Richard & Kearl, J & Vaughan, Michael. (1992). Is There a Consensus Among Economists in the 1990s? American Economic Review. 82. 203-09.

[2] Daniel P. Kessler (2004). The Effects of Pharmaceutical Price Controls on the Cost and Quality of Medical Care: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Stanford University, Hoover Institution, and the National Bureau of Economic Research.

[3] Robert B. Helms (2004). The economics of price regulation and innovation. Managed Care. 2004 Jun; 13(6 Suppl): 10-2; discussion 12-3, 41-2.

[4] Canadian Health Policy Institute (CHPI). Evidence that innovative medicines improve health and economic outcomes: focused literature review. Canadian Health Policy, April 2019. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/product_articles/evidence-that-innovative-medicines-improve-health-and-economic-outcomes–focused-literature-review-.html

[5] Douglas Clark (Mar 19, 2020). Counterpoint: Low prices won’t keep new medicines out of Canada: There is no evidence of a link between pricing, research and development, and access to medicine, says Douglas Clark. Financial Post. https://financialpost.com/opinion/counterpoint-low-prices-wont-keep-new-medicines-out-of-canada

[6] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations (Additional Factors and Information Reporting Requirements): SOR/2019-298. Canada Gazette, Part II, Volume 153, Number 17. Registration: SOR/2019-298, August 8, 2019. PATENT ACT: P.C. 2019-1197 August 7, 2019.

[7] PMPRB (2021). PMPRB Guidelines. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/pmprb-cepmb/documents/legislation/guidelines/PMPRB-Guidelines-en.pdf

[8] Health Canada (2017). Protecting Canadians from Excessive Drug Prices: Consulting on Proposed Amendments to the Patented Medicines Regulations. Page 3. Abbreviated.

[9] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations (2019).

[10] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations (2019). Page 5992.

[11] Labrie, Yanick (2020). Evidence that regulating pharmaceutical prices negatively affects R&D and access to new medicines. Canadian Health Policy, June 2020. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/evidence-that-regulating-pharmaceutical-prices-negatively-affects-r-d-and-access-to-new-medicines-.html

[12] PMPRB (2017). Meds Entry Watch, 2015. Figure A1.5 Comparison of the number of NASs available in Canada with those launched in PMPRB7, Q4-2015. Ottawa: Patented Medicine Prices Review Board.

[13] PMPRB (2020). Annual Report 2019. Figure 24.

[14] Skinner, Brett (2021). Prices for Patented Medicines in Canada and 13 Other Countries: Testing the PMPRB’s Narrative Justification for Amending the Regulations. Canadian Health Policy, August 2021. www.canadianhealthpolicy.com

[15] George A. Diamond, Sanjay Kaul (2009). Cost, Effectiveness, and Cost-Effectiveness. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:49-54.

[16] Hill SR, Mitchell AS, Henry DA. Problems with the interpretation of pharmacoeconomic analyses: a review of submissions to the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. JAMA. 2000 Apr 26;283(16):2116–21. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.16.2116 PMID: 10791503

[17] Pettitt D, Raza S, Naughton B, Roscoe A, Ramakrishnan A, Ali A, Davies B, Dopson S, Hollander G, Smith JA, Brindley DA (2016). The limitations of QALY: a literature review. J Stem Cell Res Ther 6: 4.

[18] David Cameron, Jasper Ubels and Fredrik Norström (2018). On what basis are medical cost-effectiveness thresholds set? Clashing opinions and an absence of data: a systematic review. GLOBAL HEALTH ACTION, 2018. VOL. 11, 1447828. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1447828.

[19] CIHI (2021). NHEX Database 1975 to 2021. Canadian Institute for Health Information.

[20] Canada Gazette Publications Part I: Vol. 151, No. 48 — December 2, 2017. Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations. REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT. Government of Canada. http://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2017/2017-12-02/html/reg2-eng.html.

[21] Bjarne Robberstad (2005). QALYs vs DALYs vs LYs gained: What are the differences, and what difference do they make for health care priority setting? Norsk Epidemiologi 2005; 15 (2): 183-191.

[22] Innovative Medicines Canada v. Canada (Attorney General). Federal Court Decisions Database. 2020-06-29. 2020 FC 725. T-1465-19

[23] Merck Canada Inc. et al v Canada (Attorney General), Quebec Superior Court file 500-17-109270-192.

[24] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations (2019). Page 5952-5954.

[25] Patricia M. Danzon (2018). Differential Pricing of Pharmaceuticals: Theory, Evidence and Emerging Issues. PharmacoEconomics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0696-4.

[26] Patricia Danzon, Adrian Towse, Jorge Mestre-Ferrandiz (2015). Value-Based Differential Pricing: Efficient Prices for Drugs in a Global Context. Health Economics 24: 294–301 (2015).

[27] Lichtenberg, Frank R., Pharmaceutical Price Discrimination and Social Welfare. Capitalism and Society, Vol. 5, Issue 1, Article 2, 2010. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2208666.

[28] Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Annual Report 2017. Section 3.09 Ontario Public Drug Programs. Page 491.

[29] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations (2019).

[30] NPDUIS Patented Medicine Prices Review Board February 2021 Meds Entry Watch, 5th Edition.

[31] Rawson, Nigel SB; Lawrence, Donna (2020). New Patented Medicine Regulations in Canada: Updated Case Study of a Manufacturer’s Decision-Making about a Regulatory Submission for a Rare Disorder Treatment. Canadian Health Policy, January 2020. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/new-patented-medicine-regulations-in-canada–updated-case-study—en-fr-.html

[32] PDCI (2020). Impact Analysis of The Draft PMPRB Excessive Price Guidelines. https://www.pdci.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/PDCI-PMPRB-Impact-Assessment-February-2020_Final.pdf

[33] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations (2019). Page 5992.

[34] Patricia M. Danzon, Y. Richard Wang and Liang Wang (2005). The impact of price regulation on the launch delay of new drugs – evidence from twenty-five major markets in the 1990s. Health Economics, 14: 269–292 (2005).

[35] Margaret K. Kyle (2007). Pharmaceutical Price Controls and Entry Strategies. Review of Economics and Statistics, Volume 89 | Issue 1 | February 2007 p.88-99.

[36] Patricia M. Danzon and Michael F. Furukawa (2008). International Prices And Availability Of Pharmaceuticals In 2005. Health Affairs 27, no. 1 (2008): 221–233; 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.221.

[37] Joan Costa-i-Font, Nebibe Varol, Alistair McGuire (2011). Does price regulation affect the adoption of new pharmaceuticals? The Centre for Economic Policy Research. http://voxeu.org/article/does-price-regulation-affect-adoption-new-pharmaceuticals.

[38] Nebibe Varol & Joan Costa-i-Font & Alistair McGuire (2011). Explaining Early Adoption of New Medicines: Regulation, Innovation and Scale. CESifo Working Paper Series 3459, CESifo Group Munich.

[39] Golec & Vernon (2010). Financial effects of pharmaceutical price regulation on R&D spending by EU versus US firms. PharmacoEconomics, 28(8), 615–628.

[40] Panos Kanavos, Anna‑Maria Fontrier, Jennifer Gill, Olina Efthymiadou (2019). Does external reference pricing deliver what it promises? Evidence on its impact at national level. The European Journal of Health Economics.

[41] Spicer, Oliver and Paul Grootendorst (2020). An Empirical Examination of the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Price Control Amendments on Drug Launches in Canada. Working Paper No: 200003. July 2020. Canadian Centre for Health Economics.

[42] Rawson, Nigel SB (2020). Fewer new drug approvals in Canada: early indications of unintended consequences from new patented medicines regulations. Canadian Health Policy, March 2020. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/fewer-new-drug-approvals-in-canada–early-indication-of-unintended-consequences-from-new-pmprb-regs-.html

[43] Skinner, Brett J. Consequences of over-regulating the prices of new drugs in Canada. Canadian Health Policy, March 27, 2018. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/consequences-of-over-regulating-the-prices-of-new-drugs-in-canada.html.

[44] PMPRB (2017). Meds Entry Watch, 2015. Appendix, Figure I.1 Share of NASs launched by OECD country, Q4-2015. Based on the non-PMPRB external data source: MIDAS™ database, IMS AG. http://www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/view.asp?ccid=1307&lang=en.

[45] PMPRB (2016). 2015 Annual Report. Figure 10. Average Foreign-to-Canadian Price Ratios, Patented Drugs, OECD, 2015.

[46] OECD (2017). Gross domestic product (GDP) (indicator). (Accessed on 12 October 2017). Population (indicator). (Accessed on 23 October 2017). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

[47] Canada Gazette Publications Part I: Vol. 151, No. 48 — December 2, 2017. Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations. REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT.

[48] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations (2019). Page 5992.

[49] Giaccotto et al (2005). Drug Prices and Research and Development Investment Behavior in the Pharmaceutical Industry. The Journal of Law & Economics, 48(1), 195–214.

[50] Koenig and MacGarvie (2011). Regulatory policy and the location of bio-pharmaceutical foreign direct investment in Europe, Journal of Health Economics, Volume 30, Issue 5, 2011, Pages 950-965.

[51] Rawson, Nigel SB (2020). Clinical Trials in Canada Decrease: A Sign of Uncertainty Regarding Changes to the PMPRB? Canadian Health Policy, April 2020. Toronto: Canadian Health Policy Institute. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/clinical-trials-in-canada-decrease–a-sign-of-uncertainty-regarding-changes-to-the-pmprb-.html

[52] Rawson, Nigel SB (2021). Clinical Trials in Canada: Worrying Signs that Uncertainty Regarding PMPRB Changes will Impact Research Investment. Canadian Health Policy, February 2021. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/clinical-trials-in-canada–worrying-signs-that-pmprb-changes-will-impact-research-investment.html

[53] Rawson, Nigel SB (2021). Clinical Trials in Canada: Worrying Signs Remain Despite PMPRB’s Superficial Response. Canadian Health Policy, March 2021. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/clinical-trials-in-canada–worrying-signs-remain-despite-pmprb—s-superficial-response.html

[54] Skinner, Brett J. Patented drug prices and clinical trials in 31 OECD countries 2017: implications for Canada’s PMPRB. Canadian Health Policy, August 2019. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/patented-drug-prices-and-clinical-trials-in-31-oecd-countries-2017–implications-for-canada—s-pmprb-.html.

[55] PMPRB. 2017 Annual Report. Figure 21. Average Foreign-to-Canadian Price Ratios, Patented Medicines, OECD, 2017.

[56] ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Institutes of Health (NIH). Data extracted: Aug 04, 2019.

[57] OECD.Stat. Datasets: Economic References, Demographic References. Data extracted: Aug 04, 2019.

[58] PMPRB. 2008 and 2017 Annual Reports. Tables 21 (2008) and 18 (2017).

[59] IQVIA. The Global Use of Medicines in 2019 and Outlook to 2023. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. January 2019.

[60] ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Institutes of Health (NIH). Data extracted: Aug 07, 2019.

[61] US FDA. https://www.fda.gov/patients/drug-development-process/step-3-clinical-research.

[62] Health Canada (2017). Protecting Canadians from Excessive Drug Prices: Consulting on Proposed Amendments to the Patented Medicines Regulations. Page 3.

[63] PMPRB (2016). PMPRB Guidelines Modernization: Discussion Paper. Page 6.

[64] Health Canada (2017). Protecting Canadians from Excessive Drug Prices: Consulting on Proposed Amendments to the Patented Medicines Regulations. Page 3.

[65] PMPRB (2016). PMPRB Guidelines Modernization: Discussion Paper. Page 6.

[66] Patricia M. Danzon (2018). Differential Pricing of Pharmaceuticals: Theory, Evidence and Emerging Issues. PharmacoEconomics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0696-4.

[67] Patricia Danzon, Adrian Towse, Jorge Mestre-Ferrandiz (2015). Value-Based Differential Pricing: Efficient Prices for Drugs in a Global Context. Health Economics 24: 294–301 (2015).

[68] Lichtenberg, Frank R., Pharmaceutical Price Discrimination and Social Welfare. Capitalism and Society, Vol. 5, Issue 1, Article 2, 2010. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2208666.

[69] PMPRB (2020). 2019 Annual Report. Page 46.

[70] PMPRB (2020). 2019 Annual Report. Page 47.

[71] PMPRB (2020). 2019 Annual Report. Page 47.

[72] PMPRB (2020). 2019 Annual Report. Page 45.

[73] PMPRB (2020). 2019 Annual Report. Patented Medicine Prices Review Board.

[74] Skinner, Brett (2021). Prices for Patented Medicines in Canada and 13 Other Countries: Testing the PMPRB’s Narrative Justification for Amending the Regulations. Canadian Health Policy, August 2021. www.canadianhealthpolicy.com

[75] Health Canada (2017). Page 3.

[76] PMPRB (2016). PMPRB Guidelines Modernization: Discussion Paper. Page 6.

[77] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations… Page 5948.

[78] Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations… Page 5952-5954.

[79] Canadian Health Policy Institute (CHPI). Facts about the cost of patented drugs in Canada: 2018 Edition. Canadian Health Policy, February 2019. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/facts-about-the-cost-of-patented-drugs-in-canada–2018-edition-.html

[80] CIHI National Health Expenditure Trends, 2020 — Methodology Notes. Page 9, “Drugs”.

[81] Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. Annual Report 2019.

[82] The latest data available cover the fiscal year 2018–19 excluding Quebec and Nunavut. CIHI Data tables: Trends in Hospital Spending, 2005–2006 to 2018–2019. https://www.cihi.ca/en/hospital-spending

[83] CHPI (2020). Patented Medicines Expenditure in Canada 1990-2019. Canadian Health Policy, June 2021. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/patented-medicines-expenditure-in-canada-1990-2019.html

[84] PMPRB Annual Report 2019. Figure 10.

[85] Johannesson, M. et al. (2009), Why should economic evaluations of medical innovation have a societal perspective? OHE Briefing, No. 51, Office of Health Economics, London.

[86] Canadian Health Policy Institute (CHPI). Evidence that innovative medicines improve health and economic outcomes: focused literature review. Canadian Health Policy, April 2019. www.canadianhealthpolicy.com

[87] Lichtenberg, Frank R (2016). The Benefits of Pharmaceutical Innovation: Health, Longevity, and Savings. Montreal Economic Institute. June 2016.

[88] Lichtenberg FR (2015). The impact of pharmaceutical innovation on premature cancer mortality in Canada, 2000–2011. International Journal of Health Economics and Management. September 2015, Volume 15, Issue 3, pp 339-359.

[89] Hermus G, Stonebridge C, Dinh T, Didic S, Theriault L (2013). Reducing the Health Care and Societal Costs of Disease: The Role of Pharmaceuticals. The Conference Board of Canada, July 2013.

[90] Lichtenberg FR (2012). Pharmaceutical Innovation and Longevity Growth in 30 Developing and High-income Countries, 2000-2009. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper No. 18235. July 2012.

[91] Frank R. Lichtenberg, Paul Grootendorst, Marc Van Audenrode, Dominick Latremouille-Viau, Patrick Lefebvre (2009). The Impact of Drug Vintage on Patient Survival: A Patient-Level Analysis Using Quebec’s Provincial Health Plan Data. Value in Health, Volume 12, Number 6, 2009.

[92] Pierre-Yves Crémieux et al (2005). Public and Private Pharmaceutical Spending as Determinants of Health Outcomes in Canada. Health Economics, Vol. 14, No. 2, February 2005, pp. 107-116.

[93] Lichtenberg FR (2002). Benefits and Costs of Newer Drugs: An Update. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper No. 8996. June 2002.

[94] Canadian Health Policy Institute (CHPI). Evidence that innovative medicines improve health and economic outcomes: focused literature review. Canadian Health Policy, April 2019. www.canadianhealthpolicy.com.

[95] Gowlings WLP (2021). Only the Excess – Federal Court of Appeal Criticizes PMPRB for Engaging in Consumer Protection. 04 August 2021. https://gowlingwlg.com/en/insights-resources/articles/2021/federal-court-appeal-pmprb-consumer-protection/

[96] PMPRB (February 9, 2021). Communications Plan. Posted by CORD: http://www.raredisorders.ca/content/uploads/file-2.pdf

[97] Globe and Mail. Is Ottawa prepared to call Big Pharma’s bluff? Konrad Yakabuski (June 4, 2021).

[98] Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders (CORD) (2021). PMPRB Campaign to Discredit Patients and Others Who Do Not Agree with Them. https://www.raredisorders.ca/5045-2/

[99] Savoie (2021). Report of Donald J. Savoie on Machinery of Government Issues with respect to the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, June 7, 2021. http://www.raredisorders.ca/content/uploads/Savoie-DJ-re-PMPRB-and-Duty-of-Neutrality-June-7-2021.pdf

[100] Savoie (2021). Page 3.