OPEN ACCESS

Availability and Accessibility of Essential Drugs for Rare Disorders in Canada

Nigel S B Rawson, PhD, Affiliated Scholar, Canadian Health Policy Institute

ABSTRACT

In 2021, the Rare Disease Treatment Access Working Group (RDTAWG) of the International Rare Diseases Research Consortium, a European Union funded organization, published a list of medicinal products that they considered to be essential for the treatment of rare conditions. This study assesses the availability and accessibility of the RDTAWG medicines in Canada by comparing whether the rare disorder medicines approved for marketing in the United States also had regulatory approval for the same indication in Canada, and whether those medicines are ultimately covered under the 10 provincial government drug plans and the federal Non-Insured Health Benefits plan for indigenous persons. Data available at the end of August 2021 were accessed from the relevant online drug formularies. Most (85%) of the medicines with regulatory approval in the United States were also approved for the same indication in Canada. However, only just over half were covered by either open or conditional access in government drug plans, with the proportion ranging from under 36% in Manitoba to two-thirds in New Brunswick. Approximately 20% of the medicines had open access in all the plans, whereas the proportion with conditional access ranged from 13% in Manitoba to 45% in Ontario and New Brunswick. The average rate of coverage for medicines for disorders with a prevalence of ≤1 per 100,000 was only 28%, compared with 56% for disorders with a prevalence ranging from >1 case per 100,000 persons up to 1 case per 10,000 persons, and 60% for disorders with a prevalence of >1 case per 10,000 persons. Access to many medicines regarded by experts in the RDTAWG as essential for the welfare of individuals with rare disorders is inadequate to poor in Canada, especially for ultra-rare conditions. The federal Liberals and NDP are keen to introduce some type of national pharmacare. Any program developed by Canada’s governments must ensure that Canadians will have publicly funded access to all rare disorder medicines.

SUBMITTED: September 27, 2021. | PUBLISHED: October 13, 2021.

DISCLOSURES: None declared.

CITATION: Rawson, Nigel SB (2021). Availability and Accessibility of Essential Drugs for Rare Disorders in Canada. Canadian Health Policy, October 2021. ISSN 2562-9492 https://doi.org/10.54194/HFEB4050 www.canadianhealthpolicy.com

INTRODUCTION

In 2021, the Rare Disease Treatment Access Working Group (RDTAWG) of the International Rare Diseases Research Consortium, a European Union funded organization, published a list of medicinal products they considered to be essential for the treatment of rare conditions based on approvals by key regulatory agencies in the United States, the European Union and China (Gahl et al, 2021). The RDTAWG comprises scientific experts from clinical centres of excellence in the United States, Belgium, Germany, Hungary and Spain, together with representatives of advocacy groups for persons with rare disorders.

The RDTAWG’s aim was to create a list of rare disorder medicines based on orphan designation and marketing authorization that are “efficacious, safe and having a significant impact on the quality and/or duration of life.” Conditions in the list are organized into eight categories – metabolic, neurologic, hematologic, anti-inflammatory, endocrine, pulmonary, immunologic, and miscellaneous – and include 202 medicines for 140 disorders. Drugs for rare cancers were deliberately excluded by the RDTAWG.

Since access to rare disorder medicines is commonly limited in Canada (Rawson 2017, 2020a, 2020b), this study assessed the availability and accessibility of the RDTAWG medicines by comparing whether the rare disorder medicines approved for marketing in the United States also had regulatory approval for the same indication in Canada, and whether those medicines are ultimately covered under the 10 provincial government drug plans and the federal Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) plan for indigenous persons.

METHODS

The RDTAWG list contains several medicines unlikely to be covered by Canadian government drug plans, including products used in the specialist care setting, dietary supplements, and hematological products covered by Canadian Blood Services. These medicines were excluded. The analysis was further limited to 138 medicines for 101 disorders approved for marketing for the relevant indication in the United States.

The first part of the evaluation compared whether the 138 medicines were also approved for marketing for the same indication in Canada.

The second assessed the coverage status of the Health Canada approved medicines in the 10 provincial government drug plans and the federal NIHB plan. Data available at the end of August 2021 were accessed from the online provincial and NIHB drug formularies (TABLE 1). Coverage was categorized as none, open, i.e. without use criteria, or conditional, i.e. restricted to specific types of patients.

Aggregated coverage of the rare disorder medicines in each of the provincial and NIHB plans was assessed. In addition, using prevalence estimates from the Orphanet (2021) network and reputable publications, the medicines were divided into three categories based on the prevalence of the disorder being treated (≤1 case per 100,000 persons; >1 case per 100,000 persons up to 1 case per 10,000 persons; and >1 case per 10,000 persons). The average coverage of medicines in each category was evaluated.

RESULTS

Two medicines (adalimumab and infliximab) were each listed for three indications. To avoid over-weighting these medicines in the analysis, they were included only once. In addition, cysteamine had three formulations listed, which were combined so that cysteamine was included only once. Thus, 117 (85%) of the 138 medicines with regulatory approval in the United States were approved in Canada for the same indication (TABLE 2).

TABLE 3 shows the aggregated coverage of the 117 medicines by the provincial and NIHB plans. Overall, an average of 54% of the medicines were covered by either open or conditional access. The proportion ranged from under 36% in Manitoba to two-thirds in New Brunswick. Approximately 20% of the medicines had open access in all the plans, whereas the proportion of medicines with conditional access ranged from 13% in Manitoba to 45% in Ontario and New Brunswick.

Seventeen medicines in the RDTAWG list (5-aminosalicylic acid (mesalamine), abatacept, adalimumab, amiodarone, baclofen, dexamethasone, etanercept, everolimus, golimumab, hydrocortisone, infliximab, methotrexate, methylprednisolone, penicillamine, rituximab, rosuvastatin, and tocilizumab) are also indicated for one or more common disorders. Excluding these medicines (TABLE 4) demonstrated that the overall coverage rate for purely rare disorder medicines was less than 48%.

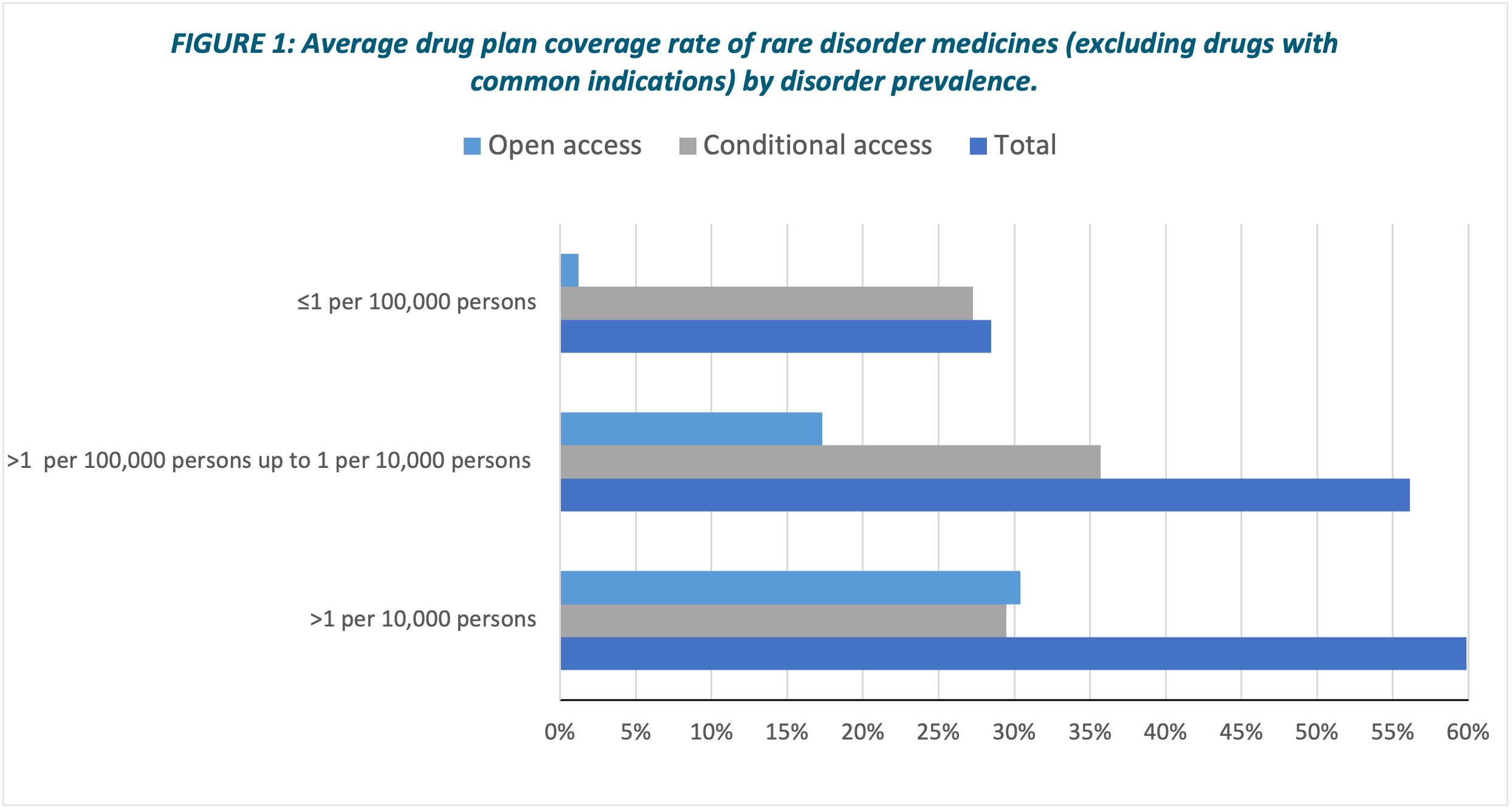

TABLE 5 shows the average rate of coverage for medicines in each plan (excluding those with one or more indications for a common disorder) in the three disorder prevalence categories. The average rate of coverage for medicines for disorders with a prevalence of ≤1 per 100,000 persons was only 28% (almost all had only conditional access), compared with 56% and 60% in the other two prevalence categories (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

This evaluation shows that 85% of the essential rare disorder medicines approved in the United States likely to be considered for coverage by government drug plans were approved in Canada. However, on average, only just over half of the Health Canada approved medicines were covered by either open or conditional access in government drug plans, with wide variation across the plans.

Some rare disorder medicines can also be used to treat one or more common disorders. It may be easier to obtain additional coverage for a rare disorder in this situation. When these medicines were excluded from the evaluation, the average coverage rate decreased to under 48%.

Coverage for medicines for disorders with a prevalence of >1 per 100,000 up to 1 per 10,000 persons and for medicines for disorders with a prevalence of >1 per 10,000 persons were broadly similar at around 50-60% in most of the drug plans. In contrast, coverage of medicines for disorders with a prevalence of ≤1 per 100,000 persons was much poorer in all the drug plans.

LIMITATIONS

This evaluation is dependent upon the coverage data being up-to-date and accessible. Some plans are updated daily, others monthly and one (Newfoundland and Labrador’s) only six monthly. However, this difference seems likely to have little impact on the results.

The ease with which formularies can be searched varies. The formularies of Ontario, the western provinces and the NIHB have online search engines, while those of the other provinces necessitate using less easily searched PDF files. Most provinces include information about medicines with conditional access in their formularies, but some have an additional PDF format list which may or may not include all conditional access drugs. For example, Ontario’s list includes only “frequently requested” medicines.

The evaluation is also dependent upon information being accessible. Drug plans are known to review patient access to some rare disorder medicines on a case-by-case basis. However, the criteria used and which drugs are dealt with in this manner are not publicly available. Consequently, it is also unknown whether whatever access is available is appropriate and fair (Rawson, 2020a).

The evaluation assumed the conditions under which a medicine is accessible were similar in each government drug plan. This holds true for many of the medicines but not all.

A few of the rare disorder medicines were approved within the past year. As a result, a health technology assessment recommendation and/or a price negotiation may not have been completed so that government drug plans are unable to decide whether to cover the medicine.

CONCLUSION

Access to many medicines regarded by clinical experts and patient advocates in the RDTAWG as essential for the welfare of individuals with rare disorders is inadequate to poor in Canada, especially for ultra-rare conditions. Why is coverage of costly drugs for ultra-rare disorders so poor?

Insurance should protect people from disastrous financial loss. In most schemes, such as car insurance, a few individuals receive major financial compensation and a small number receive some benefit, while the majority receive no benefit other than knowing they were protected from catastrophic loss.

In general, this approach applies to health care services in Canada. Governments do not limit the amount spent on health care services for Canadians with diseases such as cancer, heart conditions or COVID-19, even if their personal life choices have increased the risk of developing such diseases.

Public drug plans appear to work in a different way. Governments are comfortable with paying millions of dollars for hundreds of thousands of patients to access low-cost drugs for common disorders, such as hypertension and hypothyroidism, for which treatment adherence is commonly poor. But they are unwilling to pay for costly rare disorder medicines for a relatively small number of Canadians that can significantly improve their quality-of-life and/or extend their lives, reduce costs of health care services for often-ineffective symptom treatment, and may allow them to contribute more fully to family and society.

The election platforms of the federal Liberals and NDP indicate that they want to introduce some type of national pharmacare to improve access to drugs for Canadians. Any program developed by Canada’s governments must not be limited to medicines for common illnesses. It must also allow all Canadians to access rare disorder medicines that actually treat their condition, not just assuage its symptoms (Rawson and Adams, 2021).

[download the PDF to access exhibits]

REFERENCES

Gahl WA, Wong-Rieger D, Hivert V, Yang R, Zanello G, Groft S (2021). Essential list of medicinal products for rare diseases: recommendations from the IRDiRC Rare Disease Treatment Access Working Group. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 16: 308. https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-021-01923-0.

Orphanet (2021). Search for a rare disease. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Disease.php?lng=EN.

Rawson NSB (2017). Health technology assessment of new drugs for rare disorders in Canada: impact of disease prevalence and cost. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 12: 59. https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-017-0611-7.

Rawson NSB (2020a). Alignment of health technology assessments and price negotiations for new drugs for rare disorders in Canada: does it lead to improved patient access? Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology 27(1): e48-64. https://www.jptcp.com/index.php/jptcp/article/view/658.

Rawson NSB (2020b). Regulatory approval and public drug plan listing of new drugs for rare disorders in Canada and New Zealand. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology 27(2): e58-67. https://www.jptcp.com/index.php/jptcp/article/view/673.

Rawson NSB, Adams J (2021). Canada’s national strategy for drugs for rare diseases should prioritize patients not cost containment. Canadian Health Policy. Toronto: Canadian Health Policy Institute. https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/products/national-strategy-for-drugs-for-rare-diseases-should-prioritize-patients-not-cost-containment.html.